(October 30, 1902, San Juan de los Lagos, Jalisco – December 3, 1955, México City)

María Cenobia Izquierdo Gutiérrez is remembered as the first Mexican painter to exhibit her paintings abroad. The show took place in 1930 at the Art Centre of New York; an undisputable achievement, but it was not the only one.

María Izquierdo was an artist, a personality in Mexican culture with an attitude towards art and life.

“She resembled a prehispanic goddess. A face of sun-dried clay, smoked with copal incense. She was very well made up, with a ritual, old-fashion makeup: lips of ember, cannibal teeth, and a flat nose to inhale the delicious smoke of prayers and sacrifices, violently ochre cheeks, the eyebrows of a crow and big bags under those deep eyes. The clothing were also fantastic: purple and jet-black fabrics, lace, buttons, pendants, lavish earrings, sumptuous necklaces […] however, still, that woman with a strong resemblance to a prehispanic goddess was sweetness herself. She was shy, private” (Octavio Paz).

From family life to art life

At the age of fifteen, María Izquierdo married army officer Cándido Posadas and had three children. The family moved to Mexico City, where María took the decision to file for divorce; this was daring even for the residents of the capital at that time. At 25, she enrolled at the National School of Fine Arts, which was under the direction of Diego Rivera. She stayed there only one year. She studied specific courses like, colour and composition, and figure painting with Germán Gedovuis, who, when realising the Izquierdo’s artistic potential, let her paint at her home.

The closeness of her relationship with the teacher Gedovius faded away when María broke up with the academic nationalist perspectives in search of new compositions. This, however, was appreciated by Rufino Tamayo, who offered to teach her the watercolour and gouache techniques.

In 1929, Izquierdo had her first solo exhibition at the Modern Art Gallery of the National Theatre with the support of Diego Rivera. As the director of the National School of Fine Arts, he wrote the introduction to the exhibition in which he praised her as one the most appealing figures in the art scene. (Nevertheless, years later when she was commissioned to paint some murals in the Palace of Government of Mexico City, Rivera himself and David Alfaro Siqueiros objected that she did not have enough experience.)

In 1930, Frances Flynn Payne invited her to show her paintings at the New York’s Art Centre, where Tamayo and José Clemente Orozco had already exhibited their work. María Izquierdo chose a sample of fourteen oil paintings including portraits, still-lifes and studies. Thus, she became the first female Mexican artist to have a solo exhibition abroad. In that exhibition, the curator René d’Harnoncourt discovered her work and decided to add her to the Mexican Arts exhibition of popular art and painting which was organised that year at the Metropolitan Museum by the American Federation of Arts. This exhibition displayed the work of Rufino Tamayo, Diego Rivera and Agustín Lazo among other artists.

A style of her own

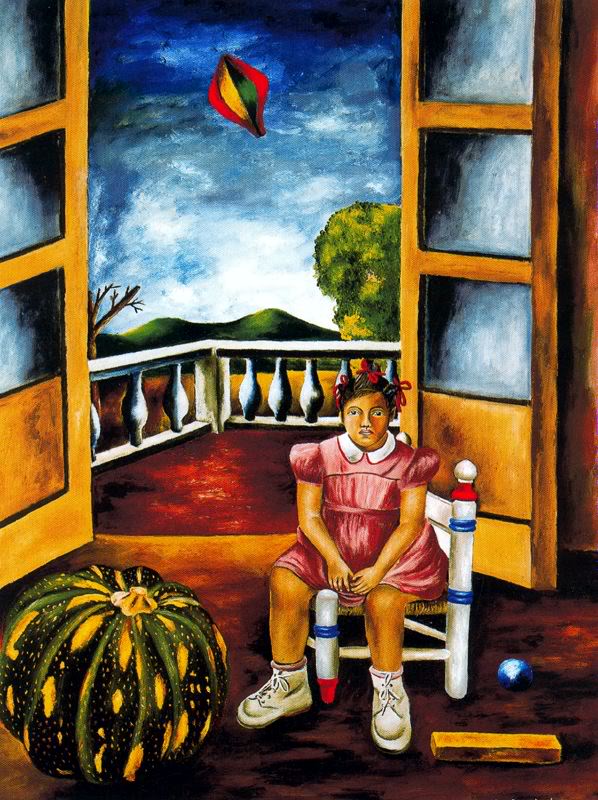

María Izquierdo soon defined her personal style away from the nationalist Mexican painting rigorousness; her work was more focused on the personal interpretation rather than prescriptive conventionalities, a crossroad that lead her to her own views. Even though the strokes were simple, even primitive for some, and the composition was naive, her painting showed a disturbing depth and a strong dose of mystery.

Octavio Paz followed the artist provincial childhood to conclude that Izquierdo’s realism was not that of history but the most real one: the one from the legend. “It is reminiscent of her childhood and rustic poetry of the towns from the centre and west of Mexico. Alive antiquity. In her case, the influences are actually convergences».

He added that “It is a work made more with instinct rather than logic. It is pure, spontaneous and fascinating like a party in a small town’s main square. A secret party that takes place not here and now, but somewhere-I-do-not-know. Interiors and still-lifes in which the objects are arranged not according to geometry, but to agreeableness. This is the magic of affection”.

“Shapes and volumes tied up to this world by an obscure desire to exist and last forever. A victory for gravitation: to be, nothing else but to be […] characters that seemed hypnotized, mythical creatures, innocent and sleepy beasts […] all submerged in a standstill atmosphere: the time that passes without passing, the time in the towns at a standstill, oblivious to the toil of history”.

The paths to art and love

Between 1927 and 1930 María Izquierdo painted still-lifes, landscapes and portraits of people closed to her, such as her daughters and her nieces in Portrait of Belem (Retrato de Belem, 1927) or Girls sleeping (Niñas durmiendo, 1930). In 1930 she started an artistic and romantic relationship with Rufino Tamayo. One Sunday, the couple travelled to Cuernavaca to see the mural that Diego Rivera was painting at the Palacio de Cortés. There, they met Luis Cardoza y Aragón and struck a friendship with him. Years later, he would remember: “They used to work in the portals of the Plaza de Santo Domingo [in Mexico City], on the second floor. At that time, there is an apparent small similarity of their work in the way they approach some shared subjects or subjects that both have in common. María has this strange gift of great sensibility with an incompetence of the trade”. The couple separated in 1933, the following year Tamayo married Olga Flores Rivas.

María’s paintings related to the earth, the roots, to the ancestral, to the choice of colours and the vigorous outline of the shapes. Contrary to a society explosive with its feelings and emotions, Izquierdo’s characters showed a hieratical solemnity.

Antonin Artaud travelled to Mexico in 1936 and was very excited about her paintings. He wrote: “Unquestionably, María Izquierdo is in communion with the true forces of the indigenous soul”. In 1937, he enthusiastically promoted the exhibition of the work of Izquierdo in Paris in the Van de Berg Gallery.

Cardoza y Aragón recalled seeing Artaud at Maria’s house, who, “generously and empathically” welcomed him while the Contemporaneos group evaded him. They were outraged by the French radicalness. “Even as drugged as he was, I noticed how pleasantly he would eat the homemade soup and nibbled tortillas with avocado”.

Despite her emotional instability, María is remembered as “cheerful, vivacious and intelligent with a personality that exuded a mixed of provincialism and sophistication”, wrote Germaine Gómez Haro.

Tradition and the avant-gardes

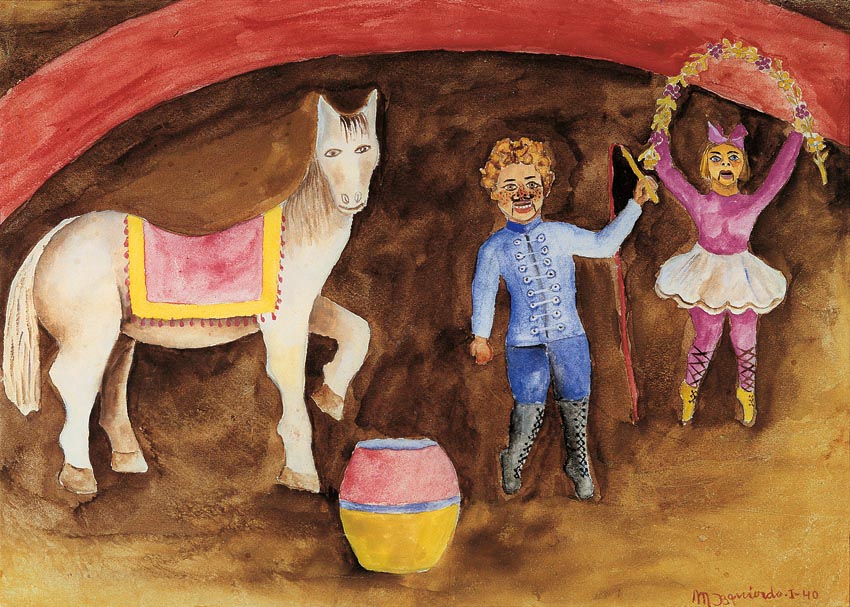

Her paintings from the 30’s were fresh, playful, with an overflown imagination, abundant in symbols, with poetic metaphors and mythical atmospheres that oscillated between melancholy and desolation. It departed from the popular folklore in order to travel towards surrealism.

Octavio Paz said that “María’s painted horses are imbued with a symbolic sexuality and passionate violence. The mythical and popular subconscious was a determining factor in her art”.

Along that line, Gómez Haro notes: “María y Rufino were interested in the qualities of the subject-matter and the exploration of colour in simple compositions associated with subjects related to the everyday life and the popular culture. Their still-lifes, landscapes and portraits reveal the deepest aspects of the Mexican soul, with a language completely opposite to that of the Mexican School (Escuela Mexicana). They also developed a metaphysic line that would link them to Giorgio de Chirico’s cryptic atmospheres, in which the characters are in unbelievable scenes or landscapes of abandon ruins and mutilated statues that permeate a mysterious air. Their naked bodies are solid and powerful…In their fantastic scenes there are amusing signs to the modern urbanite world, like planes, the telegraph, the electricity and the industrial landscape […] They took inspiration from the European avant-garde and managed to create a fascinating fusion between tradition and modernity”.

Their series of portraits and scenes of travelling circuses in rural areas have been praised.

From 1931, María Izquierdo taught in the National School of Plastic Arts of the Ministry of Public Education and joined the League of Revolutionary Writers and Artists (Liga de Escritores y Artistas Revolucionarios).

Love for the art, artists in love, art market

In 1938, she started a relationship with the Chilean painter Raúl Uribe, who she then married. Uribe became his main art dealer and helped her to sell her art to diplomats and encouraged her to paint various portraits upon request. Self-portraits and “still-lifes” were added to this work, scenes that put together dissimilar objects in mysterious, ambiguous compositions.

In 1947, Paz remembered what Artaud said about María Izquierdo: “In her paintings the real Mexico, the ancient one, the one with the subterranean rivers and sleeping craters comes to life with the warmth of blood and lava. María’s red colours!»

In 1948, María Izquierdo suffered a hemiplegia that paralysed the right side of her body and lost her speech. Her husband left her. Maria died of a stroke in 1955, in poverty.

In life, she exhibited in museums and galleries in Mexico, New York, Paris, Tokyo, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Río de Janeiro y Bombay (former name of Mumbai), among other cities. Having said that, she would also display her paintings in popular places like the bar in the nightclub Leda, in the Doctores neighbourhood in Mexico City. It was an “authentic and colourful club, but at the same time thuggish and sophisticated, where it was easier and more useful to get in than in the Spanish Academy (Academia de la Lengua), attended by proletariats and painters, poets, journalists and other various interesting characters … the thick smoked atmosphere smelled of tequila and armpits”, wrote Cardoza y Aragón.

In the 1980’s a furore for Frida Khalo raised and outshined other female Mexican painters, of which in time were hardly spoken about.

In 1988, Octavio Paz defended Izquierdo’s artistic work: “she was not an unknown nor was she a marginal artist. She was recognised by José and Celestino Gorostiza, Villaurrutia, Fernando Gamboa […] Between Tamayo, Julio Castellanos, El Corzo, Manuel Rodríguez Lozano, Alfonso Michel, Carlos Orozco Romero among other artists, María’s art and the person shone with a unique light, more lunar than solar. She seemed to me very modern and very ancient”.

Germaine Gómez Haro concluded: “María Izquierdo‘s art is the subtle symbiosis of drama and tenderness, solitude and enjoyment, violence and playfulness, primitivism and sophistication: an engrossed style, beating with life and bursting with passion”.

Sources:

Octavio Paz. Los privilegios de la vista, 1987.

Luis Cardoza y Aragón. El Río, novelas de caballerías, 1986.

Germaine Gómez Haro. María Izquierdo: pasión y melancolía, 2013.

[Gerardo Moncada]