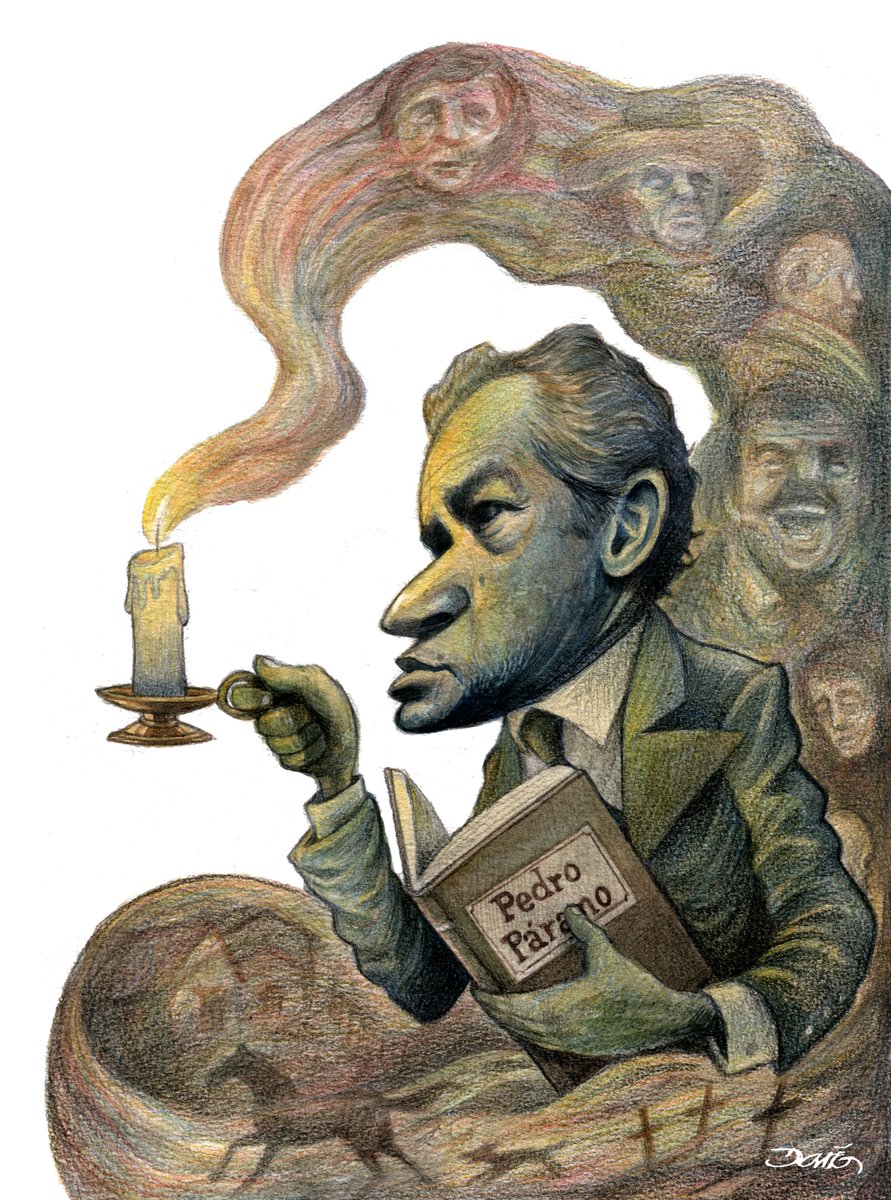

Juan Rulfo only had to write one brilliant novel to reach worldwide and everlasting fame. Today we take another look at his work, Pedro Páramo.

Pedro Páramo is one and several stories at the same time: it is the tale – with an admirable poetic charge- about the brutality of rural life in Mexico; it is a bucolic song with an avant-garde touch; it is the disenchanted vision of the Mexican Revolution; it is a requiem for the Suave Patria.

“I came to Comala because I was told that my father, a man called Pedro Páramo, lived over here. My mother had told me this, and I promised her on her death bed, that I would come to see him,”… “Do not ask him for anything. Demand that he gives you what is rightfully ours; what he should have given me and never did… Make him pay dearly, my son, for the oblivion in which he kept us”.

This novel is the forerunner of magic realism, inhabited with shadows, murmurs, echoes, rumours, voices:

“Here, those hours are full of ghosts. If only you could see the host of souls wandering free through the streets. As soon as it gets dark, they start appearing” […] “It wasn’t until I heard the words for a time that I realized, they did not have any sound, they did not make a noise, they were felt, but without sound, like the words that are heard during dreams”.

Despots and backward priests dominated the cruel rural life, where the furrows are watered with blood, where the past is rooted, omnipresent; where not even the dead are past, let alone the souls that inhabit the places:

-Did you not hear what was happening? Like someone was being murdered […]

-Perhaps it is an echo that it is trapped here. It is in this room where Toribio Aldrete was hanged a long time ago […] I do not understand how you have been able to enter, since there is no key to open this door.

-It was Mrs Eduviges who opened it. She told me that it was the only room she had available.

-Eduviges Dyada?

-Herself.

-Poor Eduviges. She must still be in torment.”

The dialogs between the living and the dead are something natural:

– In the meantime, tell the dear deceased that I always appreciated her and to remember me when she reaches heaven.

-Yes, mother Villa.

-Tell her before she gets completely cold.“And she heard the footsteps retreating, leaving her as always, with a sensation of coldness, of shivering and fear.

-Why do you come to see me, if you are dead?”

Characters of few words, once dead, they are chatterboxes, talk non-stop, remember, feel, and reflect:

-I heard someone talking. It was the voice of a woman. I thought it was you.

-It must be the one that talks to herself, the one with the large grave, Mrs Susanita. She is buried next to us. The dampness must have reached her and she must be turning and tossing in her sleep (…)

-Do you hear? It seems she is going to say something. There is a murmur.

-No, that is not her. That comes from farther away, from this other direction. And it is a man’s voice. What happens with these old dead people is that when dampness reaches them, they begin to turn and toss and wake up.-And what about your soul? Where do you think it might have gone?

-It must be wandering the earth like so many others (…) When I sat down to die, my soul begged me to get up and carry on dragging my life, as if it was still waiting for some miracle that would cleanse me of my sins. I did not even try. : ‘The road ends here, I said. I have no strength left anymore’. And I opened my mouth so my soul would go and it left. I felt when the trickle of blood which tied it to my heart spill onto my hands…“I am someone that does not bother anyone. You see, I did not even take up any space on Earth. They buried me in your own grave and I fitted perfectly into the hollow of your arms. Here in this corner where you have me now. Only, I think I should be the one who would have you in my arms. Do you hear? Out there it is raining. Don´t you feel the pattering of the rain?

-I feel as if someone was walking upon us.

-Stop being afraid. No one can scare you anymore. You should think of pleasant things, because we are going to be buried for a long time.”

These intense remembering includes moments of sensuality:

“The sea wets my ankles and goes away; wets my knees, and my thighs; it wraps its soft arm around my waist, and flows over my breasts; it embraces my neck and presses against my shoulders. Then I dive into it, completely. I surrender myself to its powerful waves, its soft caresses, all over my entire body.

-I like to bathe in the sea -I told him.

But he doesn’t understand it.”

With a keen ear, Rulfo harvested expressions from the countryside and he planted them selectively without over emphasizing the language. Being careful not to fall in costumbrista writing style, spicing up the pages with rumours, sudden events, upsets, insects, hyperbole, light ups, disappointments; with verbs like to grow gloomy ,to bustle about, to stir up a commotion, to rattle…

Pedro Páramo is the immediate forerunner to the boom in the Latin-American novel in the 1960’s. After its publication, it became one of the most reviewed, studied and discussed books. It is considered one of the most important literary works of the 20th century with editions in 28 languages.

In an interview, Juan Rulfo told Joseph Sommers:

“The main character is the town; a ghost town inhabited only by souls, where all the characters are dead: even the narrator is dead. Therefore, there are no limits between space and time. The dead do not have space or time. They do not move in space or time. In the same way they appear, they disappear. And within this confusing world, it is supposed that the souls are the only ones that will return to the world of the living (it is a popular belief)» (¡Siempre!, La Cultura en México, 15 agosto 1973).

A decade later Rulfo added:

“What I did not want was to write as it is written, but to write as it is spoken […] Pedro Páramo is a spoken language. I had to get rid of more than 150 pages before finishing it as it is. I do not know if these adjustments were needed. Sometimes I think that writers should not considered that the readers reason the same way as one does and that there are too many obstacles set for the readers to fully understand […]

“Pedro Páramo existed even before its time. It was planned; it can almost be said, approximately 10 years before I had written a single page, but it was there in the back of my mind. And there was one thing that gave me the clue to get it out, that is to say, to unthread that yarn from the ball of wool. I understood the solitude of Comala; the name does not exist. I had the idea of the name from the derivative of the words ‘comal’ (hotplate) and the ‘calor’ (heat) in that town. Comala: a place under the hot fire” (Arturo Melgoza Paralizábal, Modernizadores de la narrativa mexicana, 1984).

Other angles:

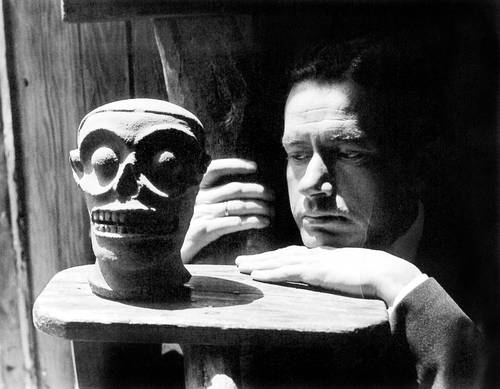

Juan Rulfo was born on the 16th of May 1917 in Sayula, Jalisco and died on the 7th of January 1986 in Mexico City.

Gabriel García Márquez wrote:

“The discovery of Juan Rulfo, like Franz Kafka´s, will be without doubt an essential chapter in my memoirs […] My big problem as a novelist was that after five barely noticed books I felt I was in a dead end and I was looking everywhere for a way out: an escape. I knew very well the good and the bad authors that would have shown me the route, however, I felt as I was going around in concentric circles. I was not feeling exhausted. On the contrary, I felt that I still had many books to write; despite this, I could not conceive a convincing and poetic world to write about. There I was, , all alone one day, when Mutis strode up the seven floors to my flat with a parcel of books, picked the smallest and shortest from the lot and mockingly told me:

Read that thing; damn it, so you learn something!

It was Pedro Páramo”.

“That night I could not sleep until I finished the second reading. Never before, since the awe-inspiring night when I read Kafka’s Metamorphosis in a gloomy student’s residence in Bogota ten years earlier, had I suffered such a shock. The following day I read The Burning Plain, and my amazement was intact […] The deep analysis of Juan Rulfo’s works finally showed me the path that I was looking for to continue with my books, and that is the reason I was not able to write about him without looking all that was about myself (Revista Proceso, Breves nostalgias sobre Juan Rulfo, 29 septiembre 1980).

In 1985, Jorge Luis Borges wrote:

“Pedro Páramo is one of the best novels of Hispanic literature and even of literature in general […] From the moment in which the narrator, who is looking for Pedro Páramo, his father, comes across with an unknown person who declares that they are brothers and that all the people of the town are called Páramo, the readers already know that they have entered in a fantastic world. They are not able to foresee its uncertain consequences, yet its gravitation pull has already magnetised them.” (UNAM/Era, La ficción de la memoria: Juan Rulfo ante la crítica, 2003)

Rosario Castellanos wrote:

It is not the fact that it had been the stage of the murders that the petty tyrant Pedro Páramo commits or orders to commit, nor the rapes of women, nor the theft of land, nor the incests, nor the go-betweens for lovers, nor the tormented lust that permeates the atmosphere. The dread of Comala is that time does not pass and that this immobility makes the characters and the situations become lifeless objects, objects over which oblivion and dust settle and in which disintegration happens so slowly that it seems like a trick of eternity. The joke of eternity being hell” (Arturo Melgoza Paralizábal, Modernizadores de la narrativa mexicana, 1984).

Carlos Monsivais wrote:

“Pedro Páramo can be classified as a novel that does not recreate a coherent vision of the world, but rather the fragmentation and collapse of the social and moral order, the survival of previous codes within a new social order, and the conflicts and confusions that arise from the mixing of the new and the old […] Instead of the universal vision of Catholicism, there are small private heavens and hells inhabited by people that can no longer make themselves heard […] at the centre of that collapse is, of course, Pedro Páramo himself […] The social structure of the feudalism is apparently preserved in Pedro Páramo but has been destroyed from within by money that imposes a new type of relation based on utilitarian values […] Here is where the tragedy of the novel lies: a past that invades the present, that persist in a ghostly way, that dries up the present time.” (La ficción de la memoria. Juan Rulfo ante la crítica, 2003).

Carlos Fuentes wrote:

“Juan Rulfo is a novelist who marks the end of some genres, not only in the sense that in Pedro Páramo he includes them, stablishing and assimilating various traditional genres of Mexican literature but with the costumbrista novel, the revolutionary novel, he also starts the modern narrative, of which he is the principal and agonistic actor […]

“According to Juan Rulfo, the American chronotope, that is, the configuration of time and space; is not a river nor a jungle, nor a city, nor a mirror: it is a grave. And it is there, from the dead, that Juan Rulfo stimulates, regenerates and makes the categories of our Hispanic American foundation modern: the epic and the myth […]

“The novel is mysterious, mystic, murmuring, agonising and mute. This is how Pedro Páramo concentrates all the dead sounds of the myth. Myth and Death: these are the two words that reign over all others even before the name Mexico itself reigns over them: an essential, unsurpassed and unsurpassable Mexican novel; Pedro Páramo comes down to the spectre of our country: a murmur of dust from the other side of the river of the Dead […]

“This novel is the story of Juan Preciado’s entrance to the kingdom of Death, not because he has found his dead, but because the Death has found him and made him part of his own education. It taught him to speak and he has learnt to identify the dead and the voices, or rather, Death as a longing for words […]

“…There has been vigorous dispute over Rulfo’s novel, a dichotomy that insists in judging it only under poetic grounds or only under political grounds without understanding that the tension of the novel is between both poles, the myth and the epic, and between two lengths of time: the duration of passion and the duration of interest […]

“To read Juan Rulfo is to remember our own dead […] then we are better prepared to understand that the duality of life and death, or that the option of life or death does not exist, but that death is part of life: everything is life. When Rulfo places death in life, in the present and simultaneously, at the origin, he is strongly contributing to the creation of a modern Hispanic American novel, this is, an open, unfinished novel that refuses to be finalised.” (La gran novela latinoamericana, Ed. PRH, 2011).

Emir Rodríguez Monegal wrote:

“Pedro Páramo is the paradigm of the new Latin American novel; a work that takes advantage of the great Mexican tradition of the land but the novel transforms it, destroys it and reconstructs it through the deep understanding of Faulkner´s techniques. It is oneiric like Onetti’s work, dangerously oscillating between the simplest realism and the unbridle nightmare. Rulfo’s novel marks a milestone.” (La nueva novela latinoamericana, 1968).

John S. Brushwood wrote:

“Pedro Páramo is brief, technically intriguing and with a profound theme […] the novel is the recount of Pedro Páramo’s bitterness and the people he tyrannised with it, even himself. Bitterness is both, the cause and the end of his power and his obsessive love for a woman. He is the incarnation of all egocentrism. Time does not exist as defined in any common meanings of the word and it doesn’t distinguish between the two states that we called life and death […]

“Rulfo uses different narrative points of view that sometimes tend to interweave with each other but sometimes they are too separated to be interwoven. One of them is the narrator in the third person, but not even he is omnipresent. The narrative fragments not only emerge from different narrative voices, but also they are in different moments of time, that are arranged, following a different kind of chronological order […]

“The language is strong, delicate, even coarse […] it captures and uses the essence of the rural language in a way that makes us accept it as authentic, but we allow it to take us from the folklore dimension to a mythical dimension in which there are no costumes but symbols […]

No other novel in Mexican literature has so skilfully handled the themes of despots and souls in purgatory. There is no doubt that Rulfo knows what he is talking about, that he understands the topic and he is able to depict its reality as it had never been shown before. […]

It is not easy for a novelist to reach the wide and profound reality of Pedro Páramo” (México en su novela, FCE, 1966).

Enrique Anderson Imbert wrote:

“In Juan Rulfo’s work, the description of external reality is shaken by the internal lives of the rural men. This way of internalising reality –men yield to their circumstances, the circumstances they find themselves in are withdrawn to their men, like nightmarish figures- is intensified in Pedro Páramo; here, Rulfo worked the theme of countryman with a complex novelistic technique that owes something to William Faulkner. The difficulty is due to being told in shifts, forwards, backwards, and from side to side and from different points of view of the narrators. The eye that knows everything and sees everything is, of course, the author, but that eye enters the novel following Juan Preciado […] Only, Juan Preciado finds out that Comala is a ghost town, empty: in the rarefied air only the voices, murmurs and echoes of ghosts can be heard. Juan Preciado himself dies and his soul carries on conversing with other souls in purgatory. The author, who has travelled to Comala as if he were descending into Hades, contemplates, as he goes, in the third person, the account of Juan Preciado. This way the author explains the voices, the echoes and the murmurs that Juan Preciado hears thanks to the scenes he invokes. The atmosphere is unearthly but it is not subjective. Time does not flow: it is everlasting. Through the open doors into that everlasting eternity, we can see and hear the dead caught in moments that do not happen like in a specific timeline, but instead are disorderly scattered: Only the reader carries on making sense of all this. The main narrative is the life of Pedro Páramo from his infancy until his death, during his old age, in the years that go from Porfirio Diaz to Obregon. It is a violent, despotic, savage, greedy, vengeful, treacherous, sensual life that is dignified by love […] The readers shiver as if they were having an absurd nightmare. The images, at times with a great poetic strength, tragically invoke the annihilation of the whole Mexican people (Historia de la literatura hispanoamericana, FCE, reimpresión de 1977).

Joseph Sommers wrote:

“Rulfo approaches the dark side of the human psyche, where the dark unforeseen thoughts reside. […] It is a nonsensical combination of a highly stylized popular language and daringly complex structure that deliberately confuses the readers in labyrinthine darkness. At times, it is hardly prose […] The result is a distinctly Mexican treatment of the tragic immutability of human anguish.

“Rulfo breaks up his narrative in disconnected small parts […] The readers have to make an effort to stablish the connections as well as being obliged to build the facts behind and the characters to extract the meaning of the apparent disorder […]

“it is in the discussion of the technique where the key to the originality of Pedro Páramo lies. The point of view, the structure, the style, the development of the character and its mystic structure; everything is combined to portray special dimensions of an implicit world view […] Death, from a narrative point of view, raises the sense of inexorability… the climax and the solution are eliminated from the beginning […] The process of multiples points of view makes it more difficult for the readers to understand the events and the impact they have on the various characters […]the entire strength of the innovative structure can be felt with the declaration of psychological weightlessness, which indicates the lack of normal basis to deal with time and reality […] The pessimistic premise is clear: Death prevails over life. In the first half, the presence of Death pollutes life, life is a living hell. In the second half, life pollutes Death, making that state also an inferno […] The essence of Rulfo’s technique is to deny its own omniscience, forcing us to share its own imperfect vision of reality and to complement it if we can […] Rulfo’s emphasis highlights aspects of popular culture endowed with symbolic references so broad in order to connect to the main aspects of universal culture […]

“Rulfo projects such deep doubts in order to question any foundation of the belief in modern society. In a world in which life has the characteristics of hell and beauty is in reality, a measurement of suffering, man’s destiny is is set in stone (La narrativa de Juan Rulfo. Interpretaciones críticas, 1974).

[ Gerardo Moncada ]* Translation: Florangeli Paredes.